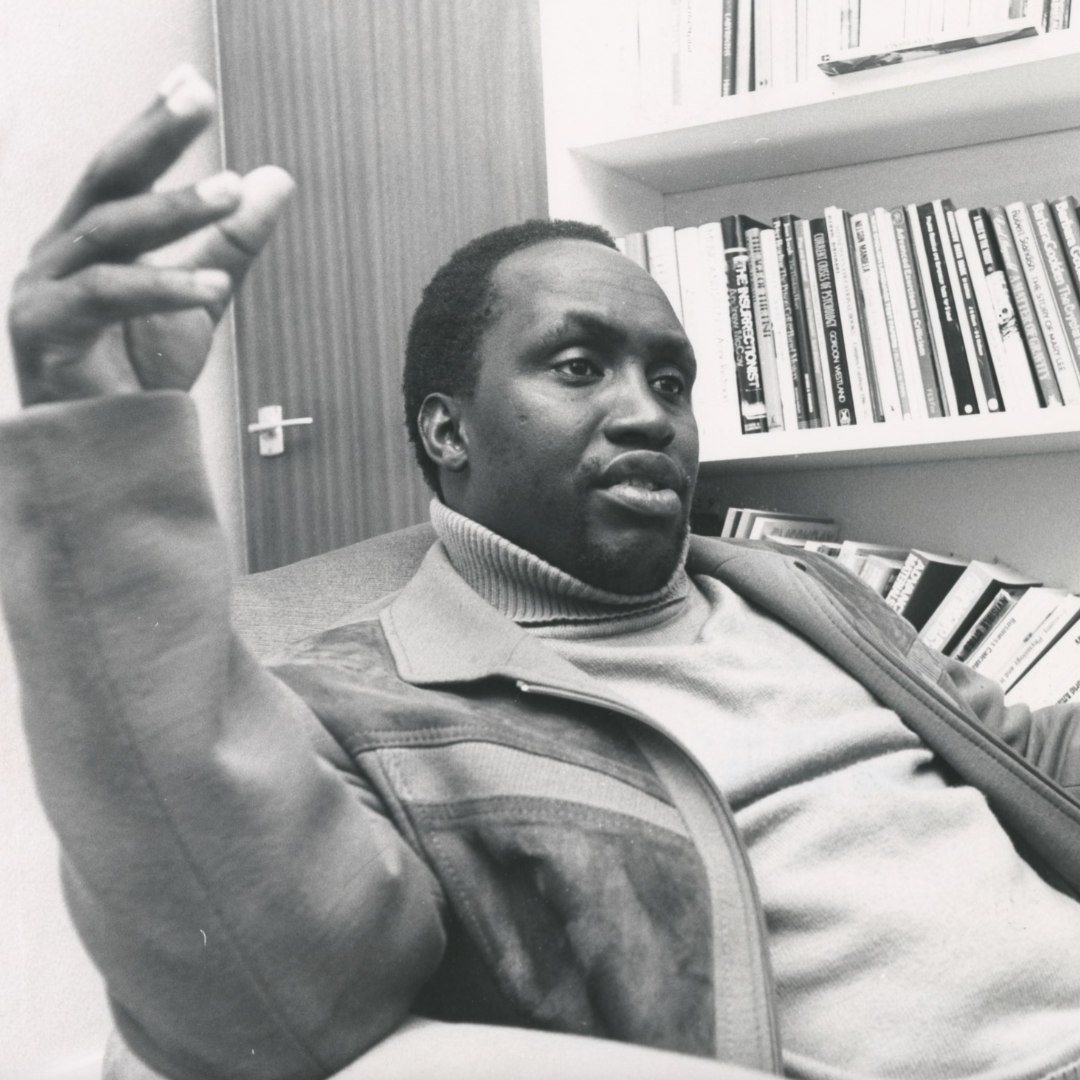

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

“I have come a long way, and I want to sleep”: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (5 January 1938-28 May 2025)

Ato Quayson, Stanford University

Like many people I knew Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o mainly from his writings, yet I feel his recent passing as a deep personal loss. There are reasons for this. I met and interacted with Ngũgĩ many times at conferences and public functions and held him in deep regard as a legend of African literature. I also kept abreast of the many wonderful stories told about him: his unbridled joy on the dance floor, his incredible sense of humor in personal conversation, and his generous mentoring of students and colleagues alike of different generations. My son’s mother is Italian and I am Ghanaian, but when he was born I suggested that we name him Kamau, after the Barbadian poet Kamau Brathwaite. Brathwaite, whose first name was originally Edward, had been given the name Kamau by Ngũgĩ’s grandmother in 1971 when he went to visit the Kenyan writer at his home while on a Visiting Fellowship at the University of Nairobi. We discovered later that the name Kamau means “the silent warrior” in Gĩkũyũ, giving the young man a great boost of confidence drawn from the subtle force of his name.

But my sense of intimacy with the legend that was Ngũgĩ did not come from any of these connections, but from the strong emotional response I had on first reading his A Grain of Wheat while studying English at the University of Ghana. At the time I prided myself on expending as little energy as possible on reading my books and doing as much of my work as I could while lying in bed. I was of the firm belief that languidness was the true mark of civilized life. The small snag in this system was that you need money to properly lead the languid life. Not having much of anything as an undergraduate, I made do with what I thought was the most proximate behavior, namely staying in bed for as many hours of the day as I could. And so, it was in bed, while reading A Grain of Wheat in my third year, that I experienced my first profound emotional epiphany as a reader.

Ngũgĩ’s novel interweaves various storylines set during Kenya’s state of emergency under British colonial rule. Many young men are accused of fighting for the Mau Mau, arrested, and put in concentration camps in appalling conditions. Gikonyo, one of the central characters detained in the novel, is from the fictional Thabai Ridge, which is rendered in the book with a tremendous sense of local texture in terms of the shifting inter-generational relationships between young and old, the mutual attraction, the flirting and the reputational quests of young males and females, the community’s response to the newly arrived iron snake (the train) that creates a contrasting rhythm between predominant rurality and the incipient signs of urbanism, and of course, the people’s growing resentment at the colonial control of their beloved Ridge and of Kenya in general. During his six years of detention, Gikonyo is sustained by thoughts of Mumbi, his beautiful wife whom he has had to leave at home. Memories of her define the very basis of both hope and resistance and so it is with great expectation, after he is finally released from the concentration camp, that he undertakes the miles-long walk back home. The changing landscape of his walk through forest, on pavements and roads is carefully detailed by the narrator, and as he approaches his homestead, we remain with him in anticipation of the meeting with Mumbi. As we are told: “Walking towards it, Gikonyo wondered what he would do when he stood face to face with Mumbi. Doubt followed excitement; what if Mumbi was at the river or the shops when he arrived. Could he possibly wait for another hour or two before he could see her?” The moment when he sets eyes on her is however nothing like he expected. Rather, it represents a complete defeat of all his great expectations and a major reversal of emotional fortunes. This is what happens: “Actually, he almost hit her at the door. She looked at him for a second or two, gave an involuntary cry, almost hoarse, and with her mouth still parted, moved back a step as if to let him in. Gikonyo saw a child securely strapped on her back. His raised arms remained frozen in the air. Then they slowly slumped back to his sides. A lump blocked his throat.” He finally enters the hut at the prompting of his mother Wangari to sit and take stock of his surroundings and what it means that Mumbi has had a child with Karanja, his friend and rival for her attention when they were younger. His mother tries to assuage the obvious turmoil in her son’s eyes by saying “These things happen.” To which he replies, simply: “I’m tired, Mother. I have come a long way and I want to sleep.” The scene of Gikonyo’s arrival describes an arc of tremulousness, from the earlier anticipation, to the near-bumping into Mumbi at the doorway, to the almost-blinding sight of a child on her back that is not his, to his forlorn gesture of first raising his arms and then letting them slump back to his sides. I suddenly sprang bolt upright on my bed as if jerked up by a force beyond me and dropped the book. My heart beat fast and I was almost in tears. I set off on a long walk on campus to process what I had just read. Ngugi had that power to rouse the reader, unsettle him, and set him in motion. He changed utterly what it meant for me to read, and he had the same effect on many.

Such a visceral reaction to a scene from literature does not come upon me often. Beside this scene from A Grain of Wheat I can also remember the one at the end of Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, when after Okonkwo’s machete falls to behead the district commissioner’s messenger, the crowd of Umuofians behind him break into tumult rather than action and he hears them asking, “Why did he do it?” At that moment Okonkwo represents an epistemological enigma to his people and is no longer the renowned warrior we have come to see him as for the previous hundred plus pages of the novel. Then there is the moment in F. Scott’s Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby when Gatsby first kisses Daisy under the night sky and suddenly experiences all of the planets in the sky as somehow being elementally aligned in that precise moment. Then there is the moment in Toni Morrison’s Beloved when Paul D shows Sethe the newspaper with the drawing of her face in it when she was jailed for slicing her daughter’s throat. Her answer to his implied question is not a yes or no, but rather an inventory of the maternal acts she has performed for her children since they were all little and at the mercy of slavery. The implication is that even the act of killing her daughter is a gesture of supreme love. I could name a few more such scenes, but what they all share for me is the combination of ambivalence, doubt, and strong emotion to suggest something like a discombobulation of the self and its loss of biographical integrity for the individual character. It takes a very masterful writer to capture such moments in a way that renders visible simultaneously their authenticity and the tenderness of human vulnerability. Ngũgĩ was definitely one of such great writers, not just in African Literature, but in World Literature in general.

II

There are some who argue that Ngũgĩ could never have won the Nobel Prize because of his political stance, especially with his essays in the highly influential and much-lauded Decolonizing the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986). I think of the matter a bit differently. After the early work – Weep Not, Child (1964), A River Between (1965) and A Grain of Wheat (1967) – his writings took a definitive turn toward forms of socialist realism and they became more strident and message-driven. Petals of Blood (1977) was designed to illustrate the rise of rural class consciousness in opposition to the bourgeois political elites in Nairobi. Devil on the Cross (1980), first written entirely in his native Gĩkũyũ, was a political allegory of the crisis in Kenya, and Wizard of the Crow (2006), also written originally in Gĩkũyũ, is set in a fictional autocratic regime and is essentially satirical and didactic. The point to note, perhaps, is that the characters in his novels in the socialist realist phase no longer expressed the tremulous emotional uncertainty that we find in A Grain of Wheat. Rather, the key protagonists emerge as clear-sighted heroes set against oppressors of various kinds. The later Ngũgĩ also intended to rouse readers, and even though they might read these works comfortably in bed, yet for me I could not respond to the characters and situations in the later novels with all the deep human feeling with which I had responded to Gikonyo. There was, I think, a certain deformation in Ngũgĩ’s writing, even if its inspiration was easily understandable: he had become more and more impatient with the state of Kenya, the land he had been exiled from for over 40 years, and with oppression in the rest of the world. This anger impacted the fictional worlds that he represented so that his work came to require a form of urgent assent to a set of propositions that did not permit either contradiction or nuance. This was very far from the remarkably human tone of the earlier novels. Ngũgĩ was a committed Fanonian Marxist for much of his life and increasingly deployed his literary works as representational illustrations of his ideology. I think that it was this, more than anything else, that blocked him from winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. If his brand of political satire prevented him from winning the Prize, he was not alone. Has the Nobel Prize for Literature ever been awarded to a satirist in its entire history?

III

Ngũgĩ’s work was heavily steeped in biblical imagery and the Bible must be considered a primary intertext of all his writings. Petals of Blood is charged with both direct and indirect biblical quotations and references, with the Christian church and its attendant education system as frequent targets of attack. Taking a cue from Ngũgĩ’s own readings of the Bible, we will be forgiven if we interpret some of the more painful events in his life as akin to stations of the cross. In 1976 Ngũgĩ helped to establish the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre, whose main focus was the organization of public theatre. The play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), co-written with Ngũgĩ wa Mirii and covering the themes of poverty, class struggle, and other related themes and published in the same year as Petals of Blood attracted the malevolent ire of the Kenyan government more than the novel did. The then Vice-President and later President Daniel arap Moi ordered his arrest and he was detained without trial in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison for a year. On leaving prison they refused to reinstate him to his position in the Department of English at Nairobi University. Conditions became so dangerous that he and his family had to move into exile in 1978, first to the UK and then to the United States. It was while in prison that he took the decision to stop writing any of his works in English but to do so only in Gĩkũyũ and to have them translated afterward. This was a watershed decision on his part that garnered him a lot of admirers all over the world and also not a few detractors. Detained, his prison diary, was published in 1981. It provides detailed descriptions of the woes and tribulations he and other political prisoners were put under but also testifies to his sheer hardiness and courage. Like Wole Soyinka’s The Man Died, it is considered a classic of the genre of prison writing in African literature.

Ngũgĩ took up a Visiting Professorship at Yale from 1989-1992 and then from 1992 became Professor of Comparative Literature and Performance Studies at NYU, holding the Erich Maria Remarque Chair. In 2002 he moved to the University of Irvine in California to take up the position of Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature and inaugural director of the International Center for Writing and Translation at the University of Irvine. These professional developments seem to have somehow obviated the pain of his and his family’s exile, but given how heavily steeped all his novels were in the natural environment of his homeland, it is also clear that this was never a straightforward matter.

The next traumatic setback came on his visit to Kenya in 2004 as part of a one-month tour of East Africa, some two years after the passing of his nemesis Daniel arap Moi. Despite his residing in a high-security apartment, thugs still managed to break into the place, assault him and rape his wife in front of him. The whole world was utterly sickened at these events, and there has been much speculation since then as to whether they were politically orchestrated or the work of vengeful family members. Whatever the truth we can assume that this homecoming after nearly twenty years, like Gikonyo’s, must have turned the very idea of his homeland to ashes.

On March 12, 2024 Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ, Ngũgĩ’s second child and himself a writer, posted on X (formerly known as Twitter) that his father had been physically abusive to Mukoma’s mother Nyambura, Ngũgĩ’s first wife. This was a heartrending revelation to many observers and took me back personally to many such scenes in my own childhood and in that of my friends. My first thoughts went to Nyambura. What must it have been like to see the intelligent and sensitive writer switch, perhaps under minor provocation, to unrestrained violence toward her? The gasps, the bewilderment, the tears, and the confusion? The sheer terror when violence was further threatened and happened again and again? Then my thoughts went to Mukoma. What must it have felt like bearing witness as a child to this violence from his father against his mother? He clearly adores his father, and it is no accident that he himself has become a writer and also a spokesperson for equity and justice whenever the opportunity has presented itself. But what long turmoil must he have endured to declare this terrible fact to the world on the social media platform, the home of sceptics and trolls of all kinds? Was it because it was of a recognition that it would be impossible to get his illustrious father to acknowledge some of the contradictions embedded in his own life as writer, father, husband, and African of that generation? Or simply as a father himself, the very loss of faith in the very principle of fatherhood? And what of Ngũgĩ himself? What must it have felt like to see his son disclose in public what may have long been the source of private angry disputes within the family? How did it feel to experience this while newly divorced from his second wife (the rape survivor twenty years earlier in Nairobi), and living alone and battling kidney failure and being on dialysis? What must he have felt when he contemplated the resentment of another writer, no other than his own son? We do not know how father and son dealt with this most delicate and painful matter and everything that has followed afterward in the public debate has been speculation, as are the words I have just written. Literature, however, can help us imagine what human contradiction and human suffering are like.

Ngugi’s memoir of childhood, Dreams in a Time of War, opens with his experience of reading T.S. Eliot, a reading which brought back to him his personal experience. In contemplating Ngũgĩ the man the haunting words from T.S. Eliot’s “Marina” come to mind:

What seas what shores what granite islands towards my timbers

And woodthrush calling through the fog

My daughter.

Eliot’s lines are inspired by the Jacobean play Pericles, Prince of Tyre, that was partially attributed to Shakespeare and provides the inspiration for his own poem, named for Pericles’s presumed dead daughter Marina. The lines imagine Pericles’s encounter with his adult daughter almost as if through a dreamlike sequence. The lines capture something of this oneiric reality, and is notable for its mixture of visual cues, “fog,” auditory cues, “the woodthrush calling,” and the vague admixture of the sense of peril, “granite islands toward my timbers,” and the relief of seeing again the long-lost daughter through the mist. I think of these lines now because they evoke something of the fragility of the bond between parents and their children that always ebbs and flows and frequently threatens to evaporate even when being grasped in celebration.

While it is clear that Ngũgĩ wa Thiongo had many flaws, it is also safe to say that he was uncompromising in the pursuit of what he saw as the truth and that he sought to deploy his writing as a penpoint in the war against oppression and ignorance of all kinds. His life shows all the markings of one we must be glad to hail as an African ancestor. Like Gikonyo he walked a very long way and deserves to Rest in Perfect Peace.

CSAAD thanks Professor Quayson for accepting our invitation to write this tribute.